Friday, November 28, 2025

A look at '50 Years of PUNK,' opening tonight at the Ki Smith Gallery

Thursday, October 24, 2024

Op-Ed: The back of our ballot in NYC

From No Power Grab NY: "The mayor's charter commission claimed that Proposal 5 was based on a recommendation from the city’s Comptroller (the city’s top financial executive)."

Friday, June 28, 2024

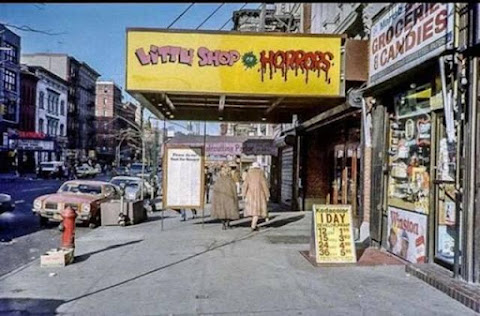

From the EVG archives: Q-&-A with Susan Seidelman, director of 'Smithereens' and 'Desperately Seeking Susan'

She went on to make several female-focused comedies, including 1985's "Desperately Seeking Susan" with Rosanna Arquette and Madonna and 1989's "She-Devil" with Roseanne Barr and Meryl Streep, among others. (She also directed the pilot for "Sex and the City.")

I spoke with Seidelman about "Smithereens" and her follow-up, "Desperately Seeking Susan," also partly filmed in the East Village, during a phone call. Here's part of that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

On why she wanted to tell this story in "Smithereens":

I was living in the East Village and I was also at NYU. And at the time, NYU Film School, the graduate film school, was on Second Avenue — part of it was where the old Fillmore East used to be. So, for three years, that area around Seventh Street and Second Avenue was my stomping grounds.

I started NYU in 1974, and I was there until 1977. So it was interesting to watch the transition from the older hippie generation and hippie-style shops and people as it started transitioning into the punk and new wave kind of subculture. I was a music person, so I frequented CBGB and Max’s Kansas City at that time. And so, that world was interesting to me, and telling a story set in that world about a young woman who’s not from that world, but wants to be part of it in some way, was both semi-personal and just of interest.

On production shutting down:

There were challenges throughout the shoot because I never had all the money. The budget ended up being about $40,000, but I probably only had about $20,000 at any given moment. I was borrowing and racking up bills. I wasn’t really thinking about how I was going to pay for it. I figured I’d get to that when I needed to pay it.

Aside from those challenges, when Susan Berman fell off a fire escape and broke her leg during rehearsal, there was no getting around that. We had to quit filming. I kind of thought, oh, you know, fuck it — I’m not going to let this stop me. It made me actually more determined. I had the time to look at what was working and what wasn’t working, and I learned a lot of stuff. I started editing the footage. I could rewrite stuff and change the story a bit.

On casting Richard Hell [a longtime East Village resident]:

That was when we redefined the character of Eric, who was originally not played by Richard Hell. It was played by somebody else who was not a rock-and-roller — he was more of a downtown painter/artsy type, not a musician — and was also played by a European actor.

By recasting and redefining that role with Richard Hell in mind, it shaped the tone of the movie and changed it, I think, in a good direction. I’m not going to give names, but the other actor — the other person is a working actor, as opposed to Richard Hell, who was acting in the movie, but was more of a presence and an iconic figure even at that time. So, trying to make the character of Eric blend in with the real Richard Hell added a level of authenticity to the film.

On filming in the East Village:

In the scene when Wren is waiting out on the sidewalk, and the landlady throws her clothing out the window and then splashes her with water, all the people and all the reactions in the background were from the people living on that block who had come out to watch.

At the time, New York was coming out the bankruptcy crisis. There weren’t a lot of police on the street, there wasn’t a lot of red tape and paperwork. These days, to film on the street, you have to get a mayor’s permit — so many levels of bureaucracy. Back then, it didn’t exist … but also I was naïve to what probably needed to be done.

We just showed up with cameras and we filmed. We had some people working on the crew who were friends and they told crowds lining in the street — just don’t look in the camera. Sometimes they did, sometimes they didn’t, but it was all very spontaneous.

That’s the advantage of doing a super low-budget movie — you can just go with the flow. For example, there’s a scene with a kid who’s doing a three-card Monte thing on the sidewalk. He was a kid we saw in Tompkins Square Park with his mother. We didn’t have to worry about SAG or unions or anything. I thought he was interesting and [we asked his mother] if they would come to this address and be in our movie.

On the lead characters:

My intention wasn’t to make likable characters. I intended to make interesting characters with some element of ambiguity. There are things that I like about Wren; on the other hand, I think she’s obviously somebody who uses people and is incredibly narcissistic. I’m aware of that. But she’s also somebody who is determined to recreate herself and to live the kind of life that she wants to live, and redefine herself from her background, which you get a little hint at, this boring suburban New Jersey life she must have run away from.

On the independent film scene at the time:

The definition of an independent filmmaker has changed so radically. Nowadays, being an independent filmmaker could mean you’re making a $5 million movie that’s really financed by the Weinstein Company, or it could mean you're doing a cellphone movie like “Tangerine.”

But back then, there weren’t that many independent filmmakers. I know there were some people working out of Los Angeles who were doing stuff and a small pocket of people in New York City. So either you knew them or you were friends with them or you just knew what they were doing and had mutual friends. It was truly a small community. And within that community, there were also a definite relationship between people who were musicians, filmmakers or graffiti artists.

So everyone was borrowing people, trading information or sharing resources. Also, the world wasn’t as competitive as it is today. People were eager and willing to help somebody who was a filmmaker would act in somebody else’s film or tell them about a location or a musician. It was pretty simple, like — hey, let’s make a movie, without a lot of calculation.

On her follow-up film, "Desperately Seeking Susan:"

I didn’t have anything lined up after "Smithereens." I didn’t know what I wanted to do next. I just finished the movie when it was accepted into the Cannes Film Festival.

But I did know that there were very few female film directors. And the one or two I had heard about who had made an interesting independent film ... I knew that your follow-up movie, especially if it was going to be financed by a studio, you needed to be smart about the choice. You had to make a movie that you could still be creatively in charge of, or else you could get lost in the shuffle.

For about a year and a half, I was reading scripts. And they were, for the most part, terrible. I just figured these couldn’t be my next movie. I have nothing to say about this kind of material.

So then I got this script. It was a little different than the way it ended up being, but it was called "Desperately Seeking Susan." I liked that the character, Susan, felt like she could be kind of related to Wren in "Smithereens." I thought I could bring something unique to that kind of a role. So I didn't feel like I was out of my element there.

Also, part of the film was set in the East Village, a neighborhood that I loved and knew. The other good thing was that I was so familiar with the characters that I was able to add my own spin using many people from the independent film community in small parts, like Rockets Redglare, John Lurie, and Arto Lindsay. Richard Hell has a cameo.

On working with Madonna:

At the time, Madonna was not famous when we started out. We were just filming on the streets like she was a regular semi-unknown actress. So there wasn’t a lot of hoopla around the film.

And then, you know, so much of life is about being there with the right thing and the right timing. It just so happened that the movie came out at the moment that her "Like A Virgin" album was released, and they coincided and she became a phenomenon. But since that wasn’t during the actual filming, there wasn’t the kind of pressure that one would normally feel if you were working with a big star or a super-famous person.

On the legacy of "Smithereens":

I think I was trying to document what it felt like to live in that neighborhood in that part of the city at that time. I never really considered whether the film would pass the test of time or be a time capsule.

But the fact that it ended up being pretty authentic to the environment, to the neighborhood, is maybe what enabled it to pass the test of time.

Saturday, April 22, 2023

The farce awakens at the Orpheum Theatre

Thursday, March 16, 2023

May the farce be with you: 'The Empire Strips Back' is next up at the Orpheum Theatre

Wednesday, March 8, 2023

Get ready to say so long to the Stomp sign

Wednesday, December 7, 2022

Bang a gone: Stomp's long run on 2nd Avenue concludes in January

"We are so proud that the East Village and the Orpheum Theatre has been Stomp's home for so many wonderful years and want to thank our producers and our amazing cast, crew and front-of-house staff, all of whom have worked so hard for so long to make the show such a success. They have always given 100 percent to every audience, from the very beginning in 1994 to the post-lockdown audiences of 2022. We want to thank everyone involved for such an incredible New York run."

Wednesday, September 7, 2022

Today in civic duty

Monday, February 28, 2022

RIP Nick Zedd

Back in 1985, Zedd coined the term the “Cinema of Transgression” to describe the campy movies full of shocking sex and violence that he and other artists like Lydia Lunch, Richard Kern, and Kembra Pfahler were making on the Lower East Side. They were scrappy movies shot on 16mm often with pornographic punchlines.Among the social media tributes...

R.I.P. Nick Zedd, the NYC underground filmmaker who coined the "Cinema of Transgression" movement. pic.twitter.com/FxsqQLPsQk

— Film at Lincoln Center (@FilmLinc) February 27, 2022

Farewell to American filmmaker Nick Zedd (1958-2022), who spearheaded the 'Cinema of Transgression' movement in the 1980s, edited the Underground Film Bulletin and joined the dots between Kembra Pfahler, Richard Kern, Tessa Hughes Freeland, Lung Leg and Lydia Lunch. pic.twitter.com/OveAVS3Jbh

— Robin Rimbaud - Scanner (@robinrimbaud) February 27, 2022

Extremely sad to hear of Nick Zedd's passing. The real deal. His work (along with Kern, Lunch, Wojnarowicz, Dick, etc) is a necessary station for anyone with even half an interest in what lies beyond the gated enclaves of boundaried taste. A mad genius of the cinema.

— thee deklane (@theedeklan) February 27, 2022

Zedd is survived by his partner of 15 years, Monica Casanova, his son Zerak and step-daughter Amanita Funaro.RIP Nick Zedd, one of the realest to ever do it. Watched all his films (and public access work 🙃) in a 24hr period a few months back and permanently broke my brain in the process. Max respect to a true underground king! pic.twitter.com/QSmGGF3pi9

— ᘻᓰᖽᐸᘿ 𝔹 (@_RareArt) February 27, 2022