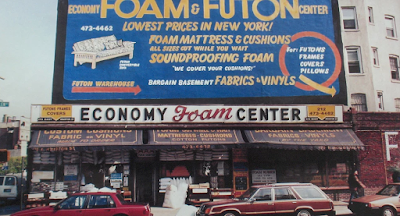

The American regionalist painters lend a lot of influence to my work. Though, they are not my only inspiration. The works of Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton were an entry point to the landscape paintings. I looked to them mostly for their formal attributes. Though, the context of their works and why they were making them do apply to my conceptual inspirations as well. These artists were producing imagery during the post-industrial revolution, capturing the turbulence of the early 20th century. The visual perspectives are skewed and the mundane American life depicted is electrified with unease.

Bosch and Bruegel are also great inspirations to me. What I see in their works is that there is no visual hierarchy. Like many of their contemporaries, a centralized figure typically dominates the composition, creating an imbalance of focus.

Fragonard’s palette is beautiful. I was recently looking at Progress of Love (1771-2) at the Frick. Such a fantastic series of works, yet, I do not have any intentional relation to Roccoco at the moment.

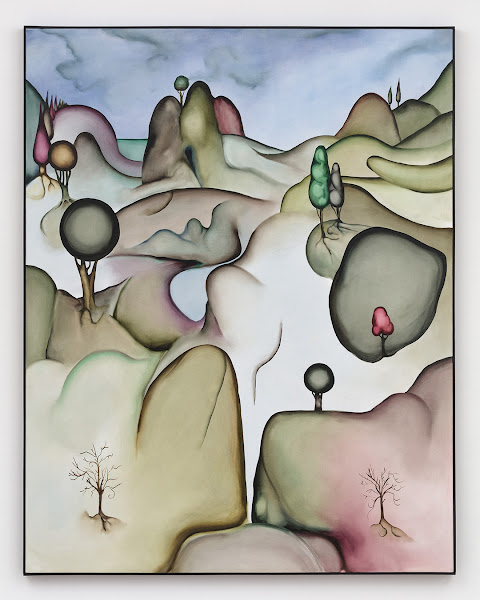

Could you break down your process in creating, say, Desk Shaped Stone (2022, above)?

Desk Shaped Stone most likely started with me drawing a few of the circular trees. From there, I would draw in hills and lines, leave some places blank and then paint from the top down, starting with the sky. I typically have an idea of the palette, but a lot is done or decided on the canvas. It is a lot of moving color and removing paint with a rag to then reapply. The act of making these works is primarily expressionistic.

This work specifically is about Bellini’s Agony in the Garden (1459-65). They say that the stone Jesus is leaning before and praying upon is shaped like a desk or an alter. That stone is depicted at the bottom of the canvas, and I also see it as two knees in a robe.

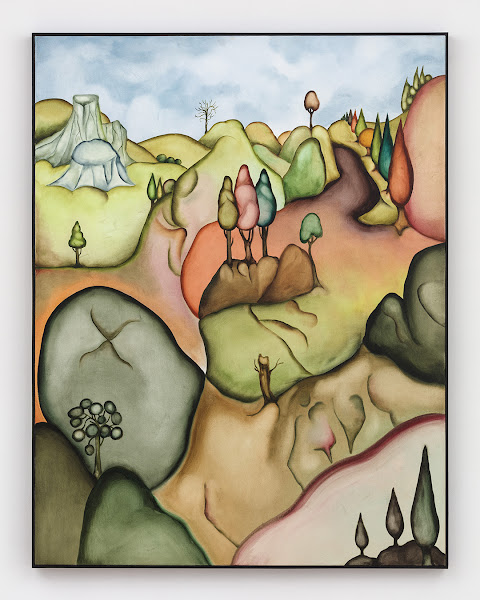

Yes. My works want to talk about the power of allegory in painting, but there aren’t any allegories in the work. Though, that may be up to the viewer’s discretion. I became fascinated with the landscapes in early renaissance paintings, which typically lay behind the figure or the symbol. These landscapes do not intend to be allegorical.

I am interested in what that implication of expanse meant back then. At the time, most people who would view these artworks had no understanding of when and where the pastoral began or ended. This feeling of boundlessness had a very different meaning to its viewers of the time. Today, we understand all-natural land to have had some sort of eyes on it or to have been documented or known to one degree or another. I wonder how we understand a ‘worldly boundlessness’ in the age of now.

I look at religious paintings through an ontological lens. I am excited about how they operated during their time of creation and how they function today. Being a visual artist, there is a lot to investigate and learn from biblical art and architecture. For example, Desk Shaped Stone may be inspired by a religious artwork, but there aren’t any images or symbols that signify anything from the bible.

For me, the phantasmagoric comes to mind when thinking about any high-fidelity artifice we engage with. Whether or not my works are phantasmagoric is up to the viewer. They do, however, want to talk about feelings of being in an altered state - ones that are not necessarily drug-induced, but rather those that are so believable yet, untrustworthy.

A Shadow Following (2022), by Erica Mao, is a work that I keep returning to and spend a lot of time with. It has a great palette and composition, and I believe its title and theme relate to my work conceptually. Erica and I had conversations leading up to the show in which we spoke about the uncanny and how specific regions are fruitful for fiction. This work definitely achieves those similarities.

Erica’s ceramics I see to be very complementary to the paintings I have in the show. There is a great relationship between the objecthood of the ceramics and the pictorial qualities of the paintings. They are exhibited on low-lying circular pedestals we designed together. The pedestals are made of slatted wood and are finished with a very dark stain. They create a great weight in the center of the show, like two mirrored wells, and the ceramics are our memories or visions of hidden sheds and geological formations we may or may not have come in contact with within our conscious reality.

What makes you gravitate toward the Hudson River School art movement? Does it hold any personal significance?

What interests me about the Hudson River School is how those artworks operated within their time. Once again, I am viewing these artworks ontologically. They utilized idealist naturalism to depict the untouched regions of the Americas, which coincided with the development of American tourism. The artworks were allegories themselves. The landscapes were soaked in the light of God. This goes back to what I was saying about the high-fidelity artifice.

Are your landscapes melting or static?

They are melting rather than static. But I wouldn’t use melting because that alludes to a singular direction of movement. I would describe them as being in a constant state of change. Different moments of perspective arrive and disappear in vignettes and blend with one another while also negating one another. The painting is a still image of this.

Atmospherically speaking, are your landscapes earthly or other-worldly? Perhaps, they are a mix of both?

I would say Earthly. They are very much our local environments. If these local environments appear to be altered, that distortion is coming from a place within rather than a place outside.